The overwhelming majority of people living in China say they are living in a democracy.

Most people in the United States say they do not.

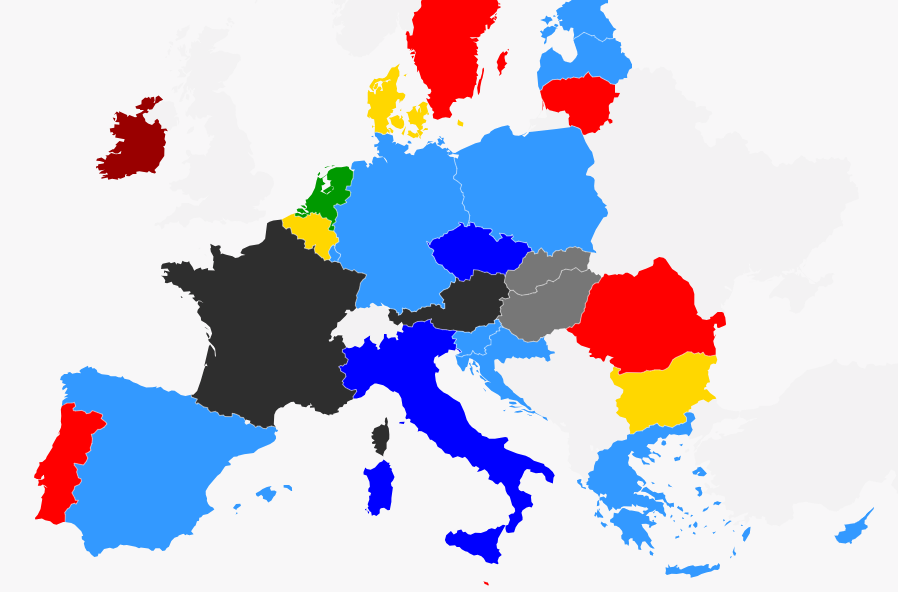

These findings are part of a new study published by the Denmark-based Alliance of Democracies Foundation and Germany-based Latana data tracking firm. Part of the latest installment of the annual Democracy Perception Index published Monday, the study explores public opinions of democracy among 52,785 respondents across 53 nations and territories, including China and the U.S., surveyed between March 30 and May 10 of this year.

When asked whether they believe their country is democratic, those in China topped the list, with some 83% saying the communist-led People's Republic was a democracy. A resounding 91% said that democracy is important to them.

But in the U.S., which touts itself as a global beacon of democracy, only 49% of those asked said their country was a democracy. And just over three-quarters of respondents, 76%, said democracy was important.

A note accompanying the poll results offers a disclaimer, stating that "in authoritarian countries, positive perceptions might result from different conceptions of democracy, high levels of government satisfaction, or fear of speaking out against the government."

Those leading the list alongside China included countries with a mix of political systems, including Switzerland, Vietnam, India and Norway. And, after the Philippines, China's rival, Taiwan, ranked high as well in terms of those who said they lived in a democracy.

Latana political research consultant Frederick Deveaux told Newsweek that the eagerness displayed by those in single-party-led nations such as China and Vietnam to describe their country as democratic "may perhaps be a function of not wanting to speak out against the government." But he argued "it could also be a real perception that their country is somehow acting in the interests of many people, and this is what democracy means."

"While some of these results are kind of surprising, it's also important to take this into account," Deveaux said, "because this will kind of determine who is winning the battle of democracy in the eyes of the public."

And, in the end," he added, "that's what matters more than if someone says, 'Actually, that's democracy, that's not democracy.'"

Other metrics in the report appeared to reinforce the sentiment that those in China expressed a more favorable opinion of their government than those in the U.S.

For instance, some 63% in the U.S. said their government mainly serves the interests of a minority, while only 7% said the same in China. Asked about whether their country held free and fair elections and offered all citizens the right to free speech, nearly a third of respondents in the U.S., 32% and 31%, respectively, said they did not, while just 17% and 5%, respectively, in China answered the same questions negatively.

And in China, a mere 5% also said not everyone enjoys equal rights in their country, as opposed to 42% who identified this same issue in the U.S.

The results come in sharp contrast to the picture the Biden administration has painted of an increasingly dictatorial China, where the ruling Chinese Communist Party was consolidating power over the world's largest population.

U.S. officials have regularly accused China of political repression, state-sponsored human rights abuses and other behaviors Washington associates with authoritarian governments. China's rapid economic development in recent decades, paired with its permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and powerful political clout, has established the nation as one of the most influential in the world.

And with that proximity to superpower status has come a growing perception in China that the U.S. was in decline. In an apparent answer to the U.S. annual human rights abuses report and other documents that heavily criticize China, Beijing has released its own reports highlighting gun violence, racism and other issues in the U.S. that Chinese officials argue erode Washington's legitimacy to comment on the affairs of other nations.

On Friday, U.S. President Joe Biden said that Chinese President Xi Jinping had warned him during a phone call after the U.S. leader's 2020 election victory. "Democracies cannot be sustained in the 21st century, autocracies will run the world."

"Why? Things are changing so rapidly," Biden quoted Xi as saying in remarks that did not reflect the readouts issued at the time. "Democracies require consensus, and it takes time, and you don't have the time."

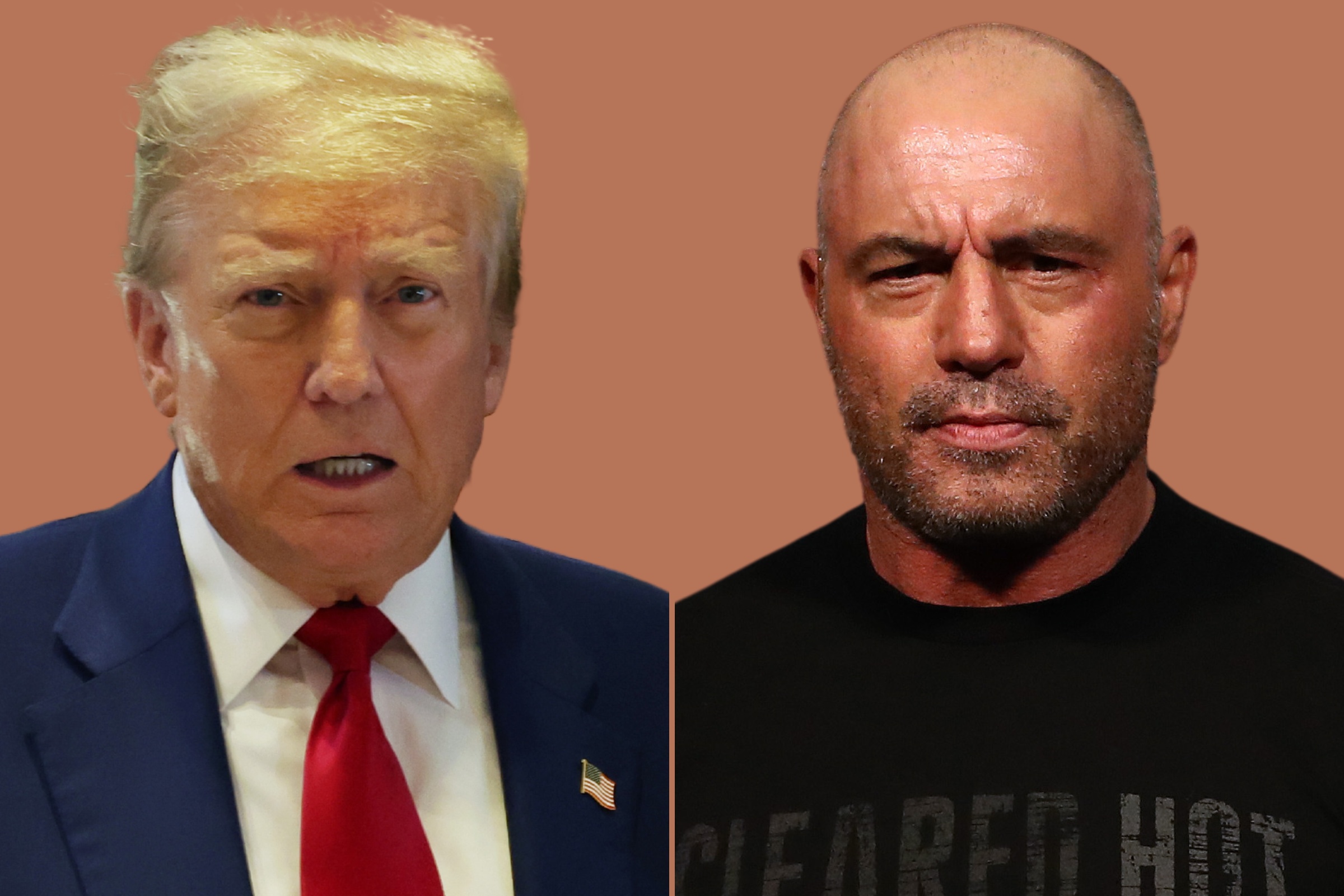

Former President Donald Trump's challenge of the 2020 election results and the subsequent storming of the Capitol building put the U.S. on the brink of a first-ever leadership crisis, and opened the country up to criticism by allies and rivals alike.

But Chinese officials have defended their country's application of democracy, while acknowledging that it differs from that of the U.S.

The Chinese Communist Party acts effectively as the sole political, legal and military authority in China, and its head, currently Xi, is not directly elected by a general vote. But the presidency, a position often held concurrently with the party's general secretary, is chosen through a ballot count as part of a tiered system of people's congresses, the highest of which determines the head of state and the lowest of which are elected directly by their constituencies.

Chinese citizens may vote directly for deputies to serve in people's congresses that oversee towns, townships, counties and cities not divided into districts, and these deputies then go on to elect deputies serving at the city level. Deputies elected to represent cities then vote for deputies at the provincial level, who then, finally, determine the deputies at the National People's Congress, the largest legislative body in the world at nearly 3,000 members.

Deputies appoint officials to leadership positions and other posts at each respective level, and, every five years, the National People's Congress votes for the president.

The system largely mirrors that of the Chinese Communist Party's own multi-layered structure, at the top of which is the National Congress, which was set to hold its 20th session in November, at which Xi is widely expected to receive an unprecedented third term as general secretary, usually viewed as the most powerful position in China. The move would also pave his way for re-election to the presidency by the National People's Congress next year.

During his last re-election in 2018, the National People's Congress removed presidential limits from the country's constitution and, last November, the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee removed similar de facto restrictions against Xi renewing his title as party boss when this year's National Congress is held.

Xi does, however, face significant challenges as he approaches a new milestone in what will soon be a decade-long tenure as paramount leader. A "zero-COVID" policy now under stress due to sporadic outbreaks has wrought disruptions in China's economy, and an increasingly antagonistic relationship with the U.S. threatened to sour Beijing's ties to the West and its partners.

Still, Xi has continued to emphasize an ongoing commitment to improving the lives of Chinese citizens and developing stronger ties with the rest of the international community.

When it comes to China's political system, the Chinese Foreign Ministry cited Xi as saying that his government has "been advancing whole-process people's democracy, promoting legal safeguard for human rights and upholding social equity and justice" during a meeting Wednesday with U.N. Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet, who is visiting China amid U.S. accusations of a state-sponsored "genocide" being committed against the largely Muslim Uyghur community.

Beijing has vehemently rejected the allegations as it sought to counter Washington's narrative and portray China as a model for global leadership in its own right.

"The Chinese people now enjoy fuller and more extensive and comprehensive democratic rights," Xi said. "The human rights of the Chinese people are guaranteed like never before."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Based in his hometown of Staten Island, New York City, Tom O'Connor is an award-winning Senior Writer of Foreign Policy ... Read more