The discovery of a mass grave in Kilkenny in 2005 told a tragic Famine story, as Jonny Geber explains. This article includes potentially distressing images.

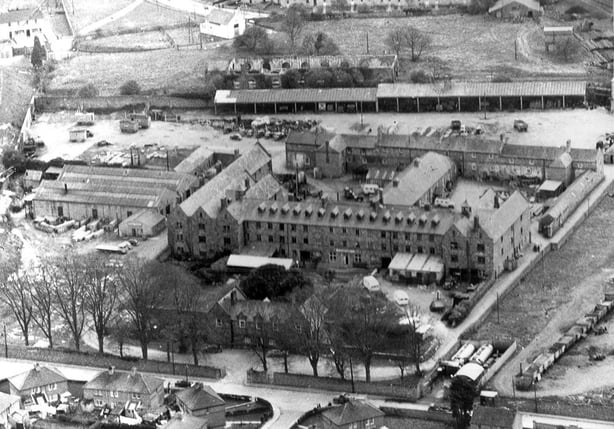

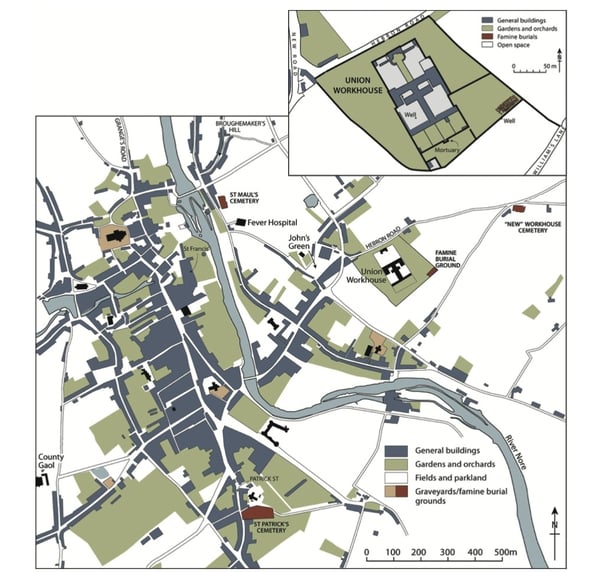

When archaeologists investigated the grounds of the former union workhouse in Kilkenny City in 2005, they witnessed a direct physical testimony to one of the most tragic social episodes in Irish history. In the ground, underneath a thick layer of sterile soil, numerous human bones and skeletons were exposed.

No local awareness that burials had taken place in the area existed. Neither were there any indications of interments noted on any maps. The complete archaeological excavation, which took place the following year, revealed the full extent of the discovery: an intramural mass burial ground comprising sixty-three burial pits for nearly 1,000 individuals that had been interred in simple pine coffins, stacked on top of each other. More than half of these interments were of children.

The interments took place between August 1847 and March 1851 and had hastily been arranged in an overflow burial ground. Mortality in the workhouse during the height of the Famine was exceptionally high, with up to sixty-eight people dying each week.

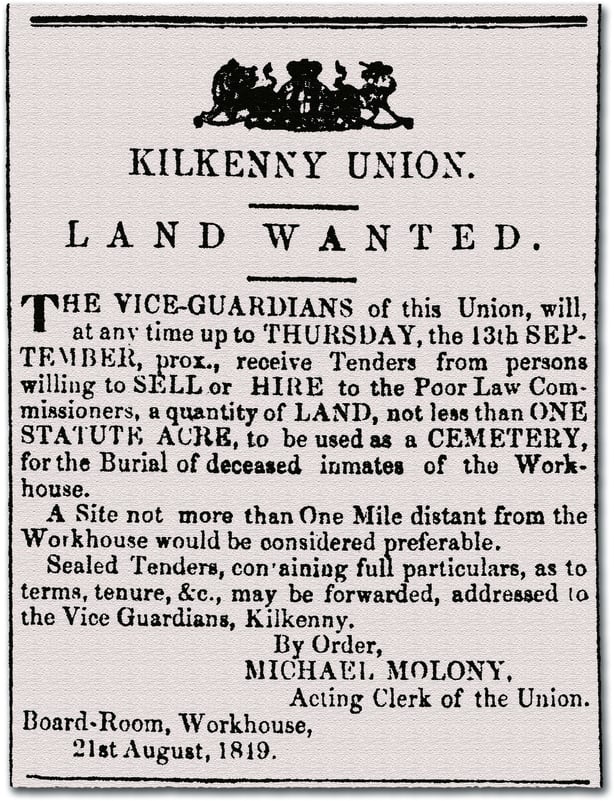

The Kilkenny Union had previously used the public cemeteries of the city, but these had become overcrowded to the extent that graves were dug too shallow and human flesh, stench, and vapours from putrefying corpses, were expelled from the ground.

The union desperately sought to establish a formal cemetery for the workhouse, but this was not achieved until mortality rates had receded back to pre-Famine levels. When a plot of land was finally procured, the intramural burial ground was immediately abandoned.

'Deserving' and truly destitute

The Kilkenny Union Workhouse opened in April 1842. It was the fifth largest workhouse institution in Ireland reflecting the fact that poverty and deprived social conditions were very much a reality, even in the eastern counties such as Kilkenny which were relatively prosperous.

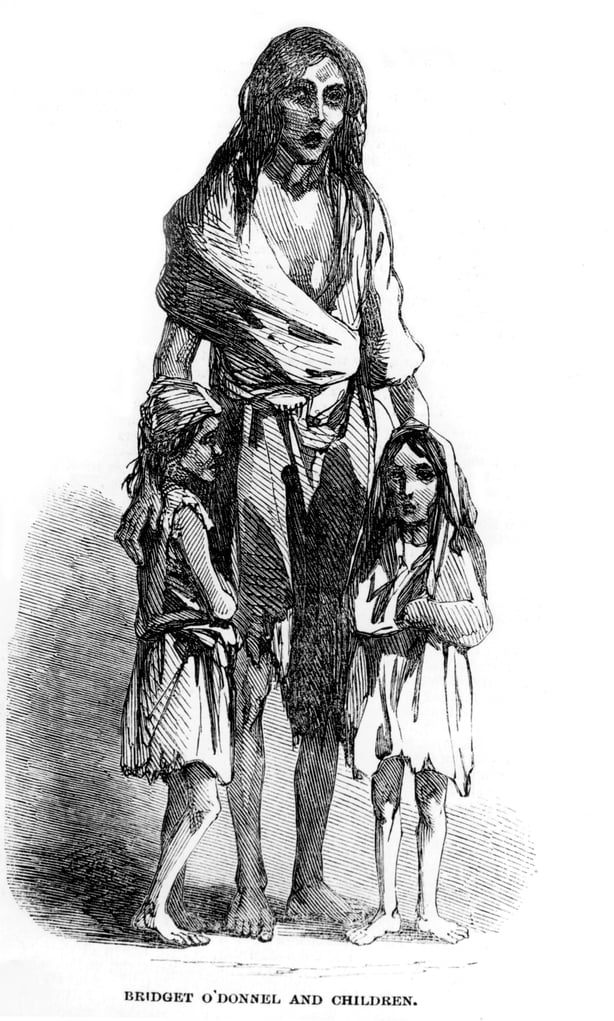

The workhouse was intended to provide relief to the poor, but only if they were "deserving" and truly destitute with no means of subsistence. Children (less than fifteen years of age) were more likely to gain access to indoor relief, and during the Famine they comprised just over 40% of the workhouse population.

The mortality of this group was high, which is also reflected in the mass burial ground. Of the 970 skeletons found in the burial pits, 522 (54%) were children. As in all Irish workhouses, the children were housed in the accommodation block at the front of the institution, but the space was not adequate and the union had to rent buildings throughout the city as auxiliary workhouses, many of which were substandard and of a deplorable state.

Following the Poor Law, children were kept separate from adults and also segregated by gender. The infants could stay with their mothers, but they were placed in the children’s wards once they had reached two years of age.

The Famine's youngest victims

The human remains in the Kilkenny mass burials provide testimony to the lives and deaths of the Famine’s youngest victims, something that is not approachable from the historical sources. The skeletons revealed numerous marks of how poverty, destitution, and famine had affected their health.

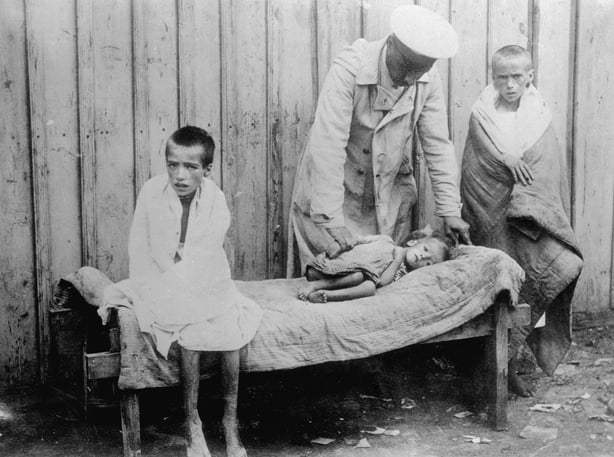

The size of their bodies, for instance, was significantly affected. An eight-year-old who died in the Kilkenny workhouse during the Famine was about the same size as an average six-year-old today. In particular, the new-borns and infants were exceptionally small for their age.

This suggests that they had suffered from intrauterine growth retardation; a condition where the poor health of starving mothers would have affected the growth of the foetus during pregnancy.

Chronic starvation

The impact of starvation on the children is also marked chemically in the collagen of their bones; nitrogen isotope values (15N) were elevated, which indicate that the many children had reached the stage of chronic starvation where the body starts to consume its protein reserve to obtain energy.

Furthermore, the impact of malnutrition was also revealed through high rates of conditions caused by nutrient deficiencies. In particular, the lack of Vitamin C - which normally would have been obtained in high quantities from the potato - resulted in scurvy that was diagnosed at very high rates in the skeletons from the Kilkenny workhouse.

Skeletal lesions due to scurvy are comprised mostly of porosity and layers of bone formed at the sites where muscle tendons attach on bone and reflect the pathophysiology of the disease as scurvy breaks down body tissue, including muscles.

Excruciating pain

Muscle trauma in those suffering from scurvy caused bruises and subcutaneous bleeding that would not recede (Vitamin C deficiency prevents the blood from coagulating), and the disease also resulted in swollen and bleeding gums, bulging eyes, dry hair and scaly skin.

Any movement would have resulted in often excruciating pain - something that the smallest children may have suffered from the most; they may have been unable to breastfeed properly. Suckling would most likely have been very painful, and the skeletons of neonates and infants often displayed considerable porotic lesions on the roof (palate) of their mouths and on their mandibles where the muscles that produce movements of the lower jaw attach.

The lack of nutrients and the increased risk of acquiring infectious diseases such as typhus, tuberculosis and cholera would undoubtedly have been major factors in the deaths of the children in the workhouse, but there may also have been other contributing circumstances.

When assessing the age-at-death profile of the skeletons in the mass burials, it is evident that there is a particular peak occurring around the age of three years. This was the age when small children were typically separated from their mothers, and the psychosocial and emotional stress associated with maternal deprivation may very well have contributed to their premature deaths.

The importance of cuddles, comfort, and affection when caring for children was first realised by the medical profession in the 1940s, and it is unlikely that the children of the overcrowded workhouses of Ireland during the Famine received the amount of emotional care that they would have desperately needed.

Painful memory

Records tell us that around 4,111 people died in the Kilkenny workhouse during the Famine, and 2,194 (53%) of these were children. The burial of nearly 1,000 men, women and children took place on the workhouse grounds, and most of the rest are likely to be interred at the nearby fever hospital where intramural burials also took place.

These burial grounds were never consecrated - something that is likely to have caused a lot of distress and added to the social trauma of the Famine and the stigma associated with the workhouse and poverty in general.

The loss of so many children may also be a factor as to why these burials were eventually forgotten; it was not only a painful memory to retain, but many children also entered the workhouses on their own as orphans or foundlings, with no family to honour their memory.

It is estimated that over 470,000 children aged less than ten years died as a consequence of the Famine between 1845 and 1852. Their experiences of starvation, disease, pain and psychological trauma are one of the most tragic aspects of this period in history, and it is clear that the subsistence crises that followed the potato blight hit the youngest generation the most. Despite this, the children have in many ways remained the ‘forgotten’ victims of the Great Irish Famine.

Jonny Geber is a lecturer in human osteoarchaeology at the University of Edinburgh. His research has a particular focus on the social bioarchaeology of the poor and marginalised in the late modern period, focusing on aspects relating to health and structural violence.

This piece is part of the Great Irish Famine project coordinated by UCC and based on the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine. Its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.